2000 FIN – Book Review: Historical Search for The Father of the Screw

November 10, 2000 FIN – The New York Times asked author Witold Rybczynski to write an essay on “the best tool of the millennium.”

Rybczynski was less than thrilled with the freelance opportunity. “I am a bit let down. The best tool is hardly as weighty a subject as the best architect or the best city, topics I could really sink my teeth into,” he recalled.

Rybczynski was less than thrilled with the freelance opportunity. “I am a bit let down. The best tool is hardly as weighty a subject as the best architect or the best city, topics I could really sink my teeth into,” he recalled.

But he wanted a break from the biography he was writing and started thinking. He and his wife, Shirley, had built a house with their own hands and they knew tools.

Rybczynski discounted power tools. Though he acknowledged that cutting all the two-by-fours for the frame of a small house would take seven days with a handsaw and only 30 minutes with a power saw, Rybczynski reasoned that hand tools “are true extensions of the human body, for they have evolved over the centuries of trial and error. Power tools are more convenient, of course, but they lack precisely that sense of refinement.”

He then considered the hammer, handsaw, drills and the box plane. He almost settled on the “boring” carpenter’s brace.

When he mentioned his indecision to Shirley, she responded without hesitation. “There is one tool that I’ve always had at home. A screwdriver,” she pointed out. “You always need a screwdriver for something.”

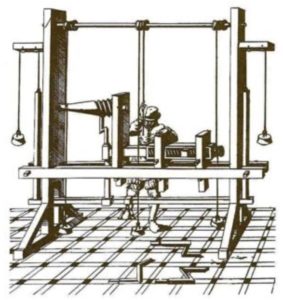

Jacques Besson’s screw-cutting machine, 1579.

Searching a thousand years of history for mentions of the earliest screwdriver proved difficult. So tough that the subject became a book, One Good Turn – A Natural History of the Screwdriver & the Screw.

Rybczynski started with William Louis Goodman’s History of Woodworking Tools and found nothing about the screwdriver until the 1800 to 1962 period. The 1949 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica only offers a definition – no history – of the screwdriver.

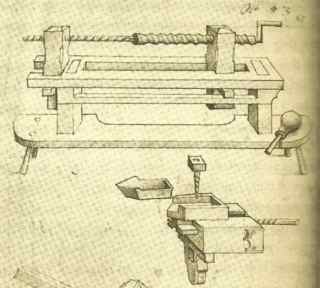

Screw-cutting lathe, from The Medieval Housebook of Wolfegg Castle, c. 1475-90

The first appearance in print that Rybczynski found was in the 1812 book Mechanical Exercises. Screwdriver is defined simply as “a tool used to turn screws into their places.” There is no illustration and no other mention in the book.

Some earlier references were not what we know as screwdrivers. The Greek word translated as screwdrivers really means “bow drills.”

There were disappointments along the way. “I am disappointed that the oldest screwdriver resembles the kind of gimcrack household gadget that is sold by Hammacher Schlemmer,” he said of a 16th century photograph.

Rybczynski found an unlabeled screwdriver in the gunsmith’s shop of the Mercer Museum in Doylestown, PA.

A catalogue by English toolmakers in Sheffield indicates there was enough demand for screwdrivers by the early 1800s to warrant factory production.

Father of the Screw

His search for the first screwdriver yielded some history of the screw.

Rybczynski observed that screws were used in early firearms instead of nails “to ensure that the lock was not loosened by the vibration of successive detonations. This use must have happened early, certainly before the 1570s.”

He found a 1505 drawing in Pollard’s History of Firearms showing moving parts fixed with rivets, but the firing mechanism fastened to the stock with four screws.

Rybczynski traces the development of the screwdriver from the Greek invention of the water screw in the second century B.C., possibly by Archimedes, to the 1936 patent for socket screws by Henry Phillips of Oregon.

Along the way there were turnscrews used for wine, olive oil, linen and printing presses. Early screwdrivers were used in Germany in war technology for armor and firearms. In the 18th century the English Wyatt brothers discovered how to manufacture screws cheaply, and Henry Maudslay created a precision screw cutter, based on a sketch by da Vinci.

Traveling tool company salesman Peter Robertson invented the Wrench-Brace, a combination brace, monkey wrench, screwdriver, bench vise and rivet maker. In 1907 he patented a socket-head screw. He got the idea for a 1907 socket-head screw patent while demonstrating a spring-loaded screwdriver to sidewalk gawkers in Montreal.

“An enthusiastic promoter, Robertson found financial backers, talked a small Ontario town, Milton, into giving him a tax-free loan and other concessions, and established his own screw factory.”

The automotive industry became a major customer.

Phillips too had been a traveling salesman. He acquired patents for Portland inventor John Thompson’s socket screw and improved the design with a cruciform shape. After rejections by many manufacturers, the American Screw Company developed it for the automotive industry, and within two years after its first use in the 1935 Cadillac all but one automobile manufacturer had switched to his socket screws.

Automakers liked the Phillips’ method, but Rybczynski noted that in a Consumer Reports testing of the Phillips and the Canadian Robertson screws rated the Robertson as “faster, with less cam-out.”

The author suggested that his favorite, the Robertson, might be the “biggest little invention of the 20th century.”

One Good Turn is an easily readable tale of a tool taken for granted.

What might interest the fastener industry most is his final chapter, which reviews literature to determine the Father of the Screw.

“The water screw is not only a simple and ingenious machine, it is also, as far as we know, the first appearance in human history of the helix. The discovery of the screw represents a kind of miracle. Only a mathematical genius like Archimedes could have described the geometry of the helix in the first place,” Rybczynski justified his choice.

“If he invented the water screw as a young man in Alexandria, and – as I like to think – later adapted the idea of the helix to the endless screw, then we must add a small but hardly trifling honor to his many distinguished achievements: Father of the Screw.” ©2000/2010 Fastener Industry News

There are no comments at the moment, do you want to add one?

Write a comment